“Life Finds A Way”

The Science and Scientists Behind Jurassic Park

It is difficult to underestimate the influence of Jurassic Park (1993) on popular culture. It is hardly an exaggeration to call it the first modern blockbuster. It heralded a new age of computer-generated wizardry in Hollywood. Its draw isn’t Arnold Schwarzenegger or Sylvester Stallone: it is the dazzling depiction of dinosaurs. In the immortal words of its tag-line: it is “An adventure 65 million years in the making.” However, its impact on public perception of science and scientists is often overlooked. What is Jurassic Park’s attitude towards technological advancement? How does Steven Spielberg portray its pioneers of de-extinction? In thus essay, I intend to explore these questions in detail. Welcome to Jurassic Park.

In his screenplay, author Michael Crichton seamlessly integrates science and science fiction. In 1993, many technologies existed only as prototypes: they are commonplace in 2015. Park attractions include self-driving, electric cars; equipped with touch-screen computers. Scientists use virtual reality (VR) displays in the workplace. Automated robotic arms display the sensitivity to grip dinosaur eggs without breaking them. The film introduced these cutting-edge concepts to a global audience of millions. Indeed, it may have served as a catalyst for investment. Google, Facebook and other Silicon Valley behemoths strive to develop similar consumer-grade products. Jurassic Park’s optimistic near-future encourages its audience to embrace these technologies. Finally, like Star Trek, the film inspired countless wide-eyed kids to pursue careers in science and engineering.

Of course, it would be churlish to ignore Jurassic Park’s foremost scientific advancement – the “miracle” of genetic engineering. At its release, the field remained in an embryonic state. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was invented a decade previously; however, its clinical use remained years away. By 1989, the knockout mouse had been developed at Harvard. Its p53 gene suppression led to oncogenic effects. In 1990, The Human Genome Project formally began. But its progress was painfully slow. Frustrated geneticist Craig Venter hastened its glacial pace with radical “shotgun sequencing” at the private company Celera Genomics. The project was completed by 2000 – three years ahead of schedule.

Jurassic Park illustrates the reliance of scientific advancement on private investment. InGen’s requires significant financial backing. And no government would willingly contribute public funding to such an over-ambitious, ethically-dubious proposition. However, the film exposes the fragile reality of such investment. In the opening scene, a maintenance worker is violently eviscerated by a raptor. The subsequent lawsuit highlights security concerns about the park’s safety. InGen’s very existence is contingent on the satisfaction of its stakeholders. This demonstrates the company’s vulnerability: a drop in investor confidence could mean the end of Jurassic Park. That could set back genetic engineering by a decade. This vulnerability is evident in contemporary biotechnology companies. In 2015, a precipitous stock market fall in China drastically devalued publicly-held firms across the world. Jurassic Park shows a surprisingly nuanced approach to private investment. It is as a necessary evil. Pioneering scientific research thrives with monetary assistance. But private funding remains a fickle and unreliable source of revenue.

Jurassic Park also offers rich and varied depictions of its scientists. In this essay, I will focus on six scientists: Ingen CEO, Dr John Hammond; Dr Henry Wu, a genetic engineer; “rockstar” mathematician, Dr Ian Malcolm; computer scientist Dennis Nedry; palaeobotanist, Dr Ellie Sattler; and palaeontologist Dr Alan Grant.

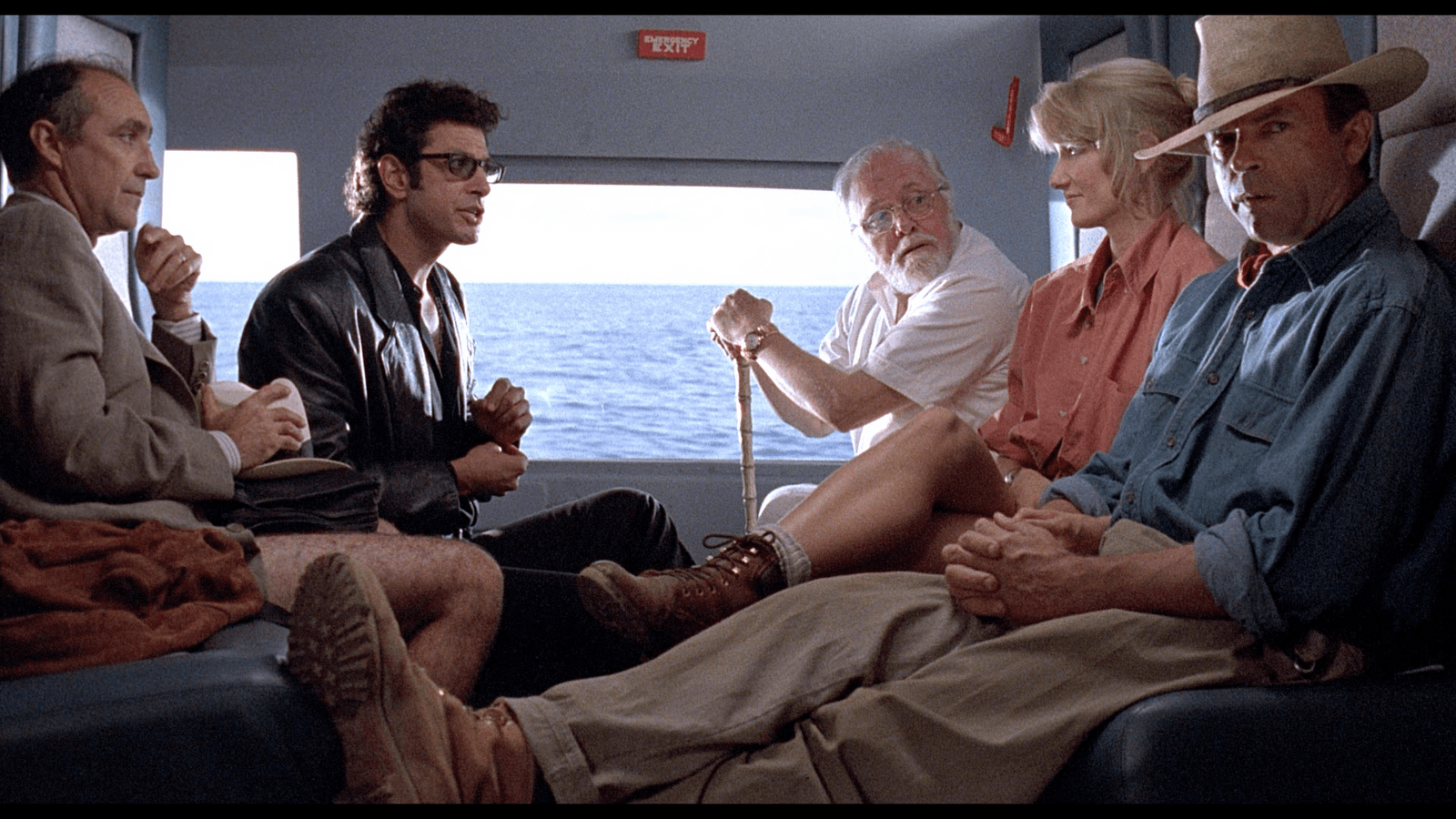

Dr Hammond, played by Richard Attenborough, characterises the idealism of scientific advancement. His investors wish to charge $10,000 a day for park admission. Hammond balks at this blatant price-gouging. “Everyone in the world has a right to enjoy these animals,” he proclaims. Like selfless virologist Jonas Salk, he is not motivated by money. Through his creations, Dr Hammond wishes to enrich the lives of all mankind. But Dr Hammond is also a duplicitous charlatan. He built his fortune operating a flea circus in London’s Petticoat Lane. Children believed the motorised contraceptive was indeed operated by hundreds of choreographed fleas. Hammond profited from their gullibility. In conversation with Drs Grant and Sattler, he deceptively describes Isla Nublar as a “biological preserve”. He believes this is necessary to convince them to inspect the island. But on their arrival, he reveals it to be “the most advanced amusement park known to man”. Dr Hammond has high-minded goals. But he is not above overt manipulation.

Dr Henry Wu (B.D. Wong) personifies the hubris of mankind. As a genetic engineer, he is directly responsible for the “miracle” of de-extinction. Dr Wu believes man can exert total control over nature. He attempts “population control”, engineering the island’s dinosaurs to be all female. He inserted a faulty gene in each species to inhibit lysine metabolism: dinosaurs thereby rely on humans for a lysine-rich food supply. He sees himself as a modern day Messiah, bringing Lazarus species back from the dead. He believes himself to have god-like powers, determining gender and survival. He brusquely dismisses any doubts cast over the project. Sadly, he is guilty of self-deception. His arrogance causes the death of five innocent civilians. Yet he remains unpunished: in 2015 sequel, he re-appears as Chief Geneticist of Jurassic World.

Dr Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) provides a welcome counter-point to Drs Hammond and Wu. Goldblum plays the character with aplomb. Wearing sunglasses and a leather jacket, he is closer to Bono than George Boole. Malcolm is a non-stereotypical mathematician: charming, charismatic – even sexy. This is fun, positive portrayal of an ostensibly boring profession. The film-makers should be commended. Malcolm is outspoken. He castigates the researchers for their myopia: “Your scientists were so pre-occupied with whether or not they could – they never stopped to think whether or not they should.” Dr Malcolm specialises in Chaos Theory: he reasons that an accident is not only possible, but inevitable. He exposes the folly in the illusion of control. Millions of uncontrollable variables mean that Wu’s plans are doomed to failure. Wu could not predict a massive tropical storm. Nor could he foresee a computer glitch that would render electric cars unresponsive. Nor could he imagine that Dr Grant would exit the unlocked car mid-tour. All these tiny oversights lead to a disaster: that night, Grant’s life is at the mercy of a Tyrannosaurus rex. And in Malcolm’s words: “You can’t suppress 65 million years of gut instinct”.

Dennis Nedry demonstrates the immeasurable skill of computer programmers. Nedry single-handedly codes Jurassic Park’s main program. Two million lines of programming amount to a remarkable technological feat. (Even if his workstation littered with sweets and fizzy drinks.) However, Nedry feels unappreciated and underpaid for his work. Wayne Knight is better known as Seinfeld’s nefarious Newman. In Jurassic Park, he also portrays a treacherous villain: Nedry plots to steal fifteen dinosaur embryos. He sells them to Ingen’s rival for an eye-watering $1.5 million. He betrays Dr Hammond’s trust. He puts countless lives in peril by shutting down the island’s electric fences. His greed and corruption prove fatal to himself and three others. However, computer science is not solely the domain of renegades. Jurassic Park portrays other computer experts in a more admirable light. Ray Arnold (Samuel L. Jackson), heroically risks his life to restore power to the island. And teenage hacker, Lex Murphy (Arianna Richards), uses her knowledge of UNIX to lock the compound’s security doors. These acts save the lives of the island’s remaining inhabitants. Programming prowess has the potential for good, or evil.

Dr Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern) is a superb female role model. She maintains a healthy lifestyle – Crichton’s script describes her as “athletic”. She an accomplished academic, receiving a Ph.D in Palaeobotany. Her career is progressing successfully. She is romantically entangled with Dr Grant, but does not let this impede her work. At the outset of the film, the couple discover a remarkably well-preserved Velociraptor nest at a Montana. However, this dig site is heavily reliant on philanthropy: Dr Hammond spends $50,000 a year to fund their excavation. But Dr Sattler is a strong negotiator. She agrees to inspect Isla Nublar in exchange for three years’ full funding.

Dr Sattler is inquisitive. She observes that a sick Triceratops has dilated pupils and macrovesicles of the tongue. She learns of its symptoms – imbalance and laboured breathing. And she examines a stool sample – with gloves, thankfully. Her investigations reveal that it is suffering from West Indian lilac toxicity: in lieu of stones, the dinosaur ingests the berries to aid its digestion. She chastises Dr Hammond for planting this poisonous shrub simply because “it looks good.” Finally, she is brave and selfless. She risks her life to rescue Dr Grant and other from a rampaging T. rex.

Dr Alan Grant (Sam Neill) is the film’s hero. In a departure from Hollywood norms, he is not some macho action star – he is a humble palaeontologist. He is intelligent and open to new ideas. For decades, people assumed that dinosaurs evolved into modern reptiles. Its Greek origin deinos sauros literally translates as “terrible lizard”. Grant challenges these assumptions. Hollow vertebrae and a retroverted pubic bone indicate that Velociraptor is more closely related to modern birds. In reality, subsequent research has proven him correct: recently discovered quill knobs on fossils reveal that raptors even had feathers.

However, Dr Grant is not perfect. An impetulant boy dismisses Velociraptor as a ‘six foot turkey’. Grant responds by terrifying the child with a raptor claw. He reveals his disdain for children – ‘noisy, messy and expensive’. Ellie is unimpressed. She doubts whether her partner is “husband material”. But Grant saves young Lex and Tim Murphy from the deadly T. rex. He reassures Lex that he won’t abandon them, as the greasy lawyer did. And he brings them back to safety. On the helicopter, the kids sleep soundly on either side of him. Ellie realises that he his attitude has matured.

Like all of us, Grant initially fears change: he worries that Jurassic Park could make his work ‘irrevelent’. Malcolm jokes that palaeontologists will soon be ‘extinct’. But like Nature itself, he grows and adapts during his experience at Jurassic Park. Tim innocently asks Dr Grant ‘what will you do if you can’t dig up fossils anymore’. “I don’t know,” admits Grant, “I guess we’ll have to evolve too.”

Leave a comment